My surname has always been something of a mystery to me. From as young as I can remember, I was very aware that it was odd – I learnt at an early age that it always had to be spelled out, and I have known the NATO phonetic letter for ‘s’ (Sierra) since long before I knew what NATO was, as on the phone (remember in the 1990s phones were still things you spoke on) ‘s’ sounds an awful lot like ‘f’, and we were always getting post addressed to ‘Omiffi’. I’ve also had O’Missi on occasion and my very favourite – and I swear that this is true – is the letter I once received addressed to a Mr (as I was then) Osmosis.

In recognition of the approaching onset of middle age, I recently got into researching my family history. My goal in this was fairly clear: to try to establish where on earth my surname comes from. I have only ever known the history of my family as far as oral tradition allowed, which in the case of my paternal line is a few half remembered snatches told to me by my father of what his father had told to him. From that I knew that that part of my family that has given me the name Omissi is a Scots-Italian one. My grandfather’s name was Giannino and he was born in a hilltop village in the Tuscan countryside, but he spoke – and smoked – like a Glasgow dock worker.

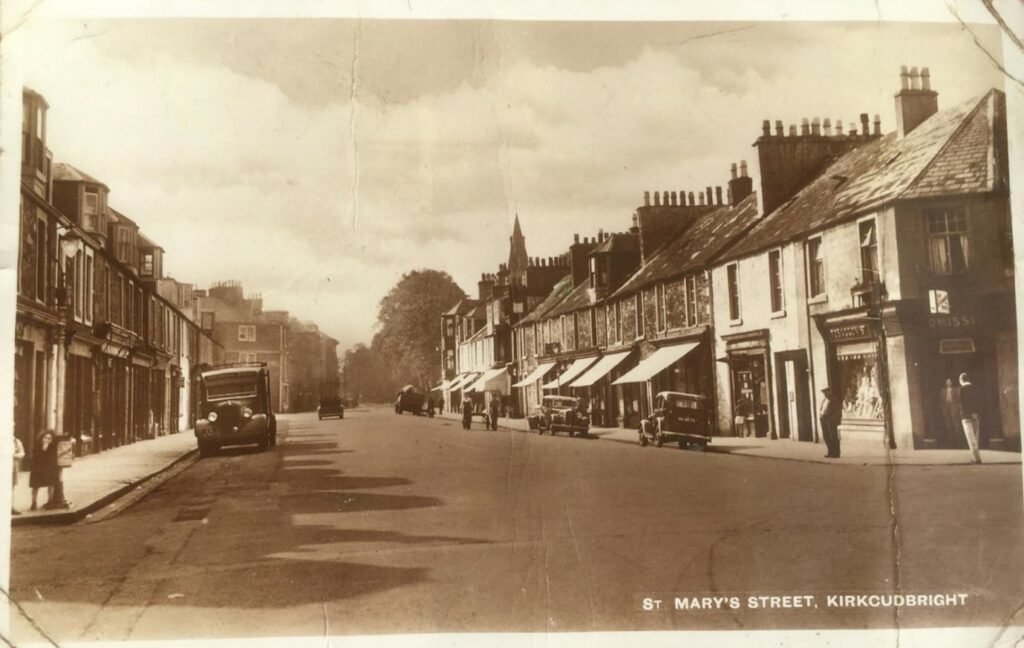

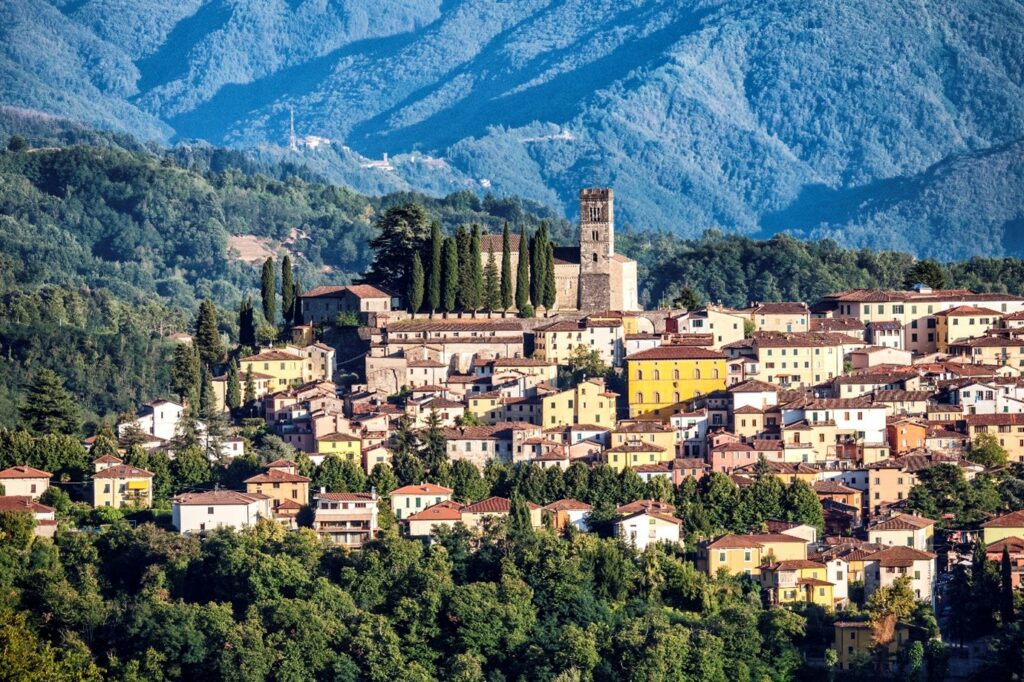

Italian immigration to Scotland in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was so extensive as to have left a considerable impact on both countries. After unification, Italy was a desperately poor country, and the agrarian crisis of the 1880s sent many Italians overseas in search of better fortune. The Italian community in Scotland came largely from two very specific regions: from Picinisco in Lazio, and from Barga in Tuscany. My ancestors came from the latter, as, I learn, did Paolo Nutini’s, and if you been to the famous Nardini’s ice cream parlour in Largs (very much worth a visit) then you’ve enjoyed the fruits of Barga’s diaspora. Like very many of the Italians in Scotland, my great grandfather, Enrico, was a café owner: Omissi’s, in Kirkcudbright.

None of this, of course, gets us any closer to the origin of the name. The trouble we have here is that it seems to be the case that everyone on the planet in possession of this name is a member of my immediate family. This was a suspicion when I was growing up, though one without a firm basis in fact, and the advent of Google and of social media in the early 2000s seemed to have confirmed it beyond reasonable doubt. So where on Earth (quite literally) did this name come from?

Which brings us back to genealogical research. Two minutes spent on myheritage.com in February of this year immediately revealed to me a previously unknown ancestor, Giovanni Omissi, my great great grandfather, who was married to a woman name Teresa Danesi. My great great grandmother’s heritage was a doddle, and within less than an hour I had traced Danesis going back into the 17th century. But patrilineal naming conventions being what they are, sadly maternal lines were no help. I needed to trace the paternal line, and Giovanni seemed to be a dead stop. No matter what website I used, I could find no listed ancestors for Giovanni.

So far, so frustrating. But as I always tell my students, don’t believe any piece of information that you cannot verify for yourself. All these genealogy websites told me that Giovanni was born on 25th June 1851 in Barga. So I decided to cut the websites out of the picture and go back to the primary sources. If he was born in Barga, then the Archivo di Stato di Firenze (the State Archive in Florence) would have a record of his birth in the files of the commune of Barga, and that record would contain the name of his father. It being 2024, one can peruse these records from anywhere in the world, old microfilms now digitised.

Giovanni, it turned out, was not born in Barga; no record of his birth (Teresa Danesi, my great great grandmother, was there right where I expected her). So I now started browsing for any record of the events of Giovanni’s life, and by patiently combing through the archive I was slowly able to pull out the record of his and Teresa’s marriage and of the birth and baptismal records of their children. Here at last came an answer for Giovanni’s lack of forebears: whilst Teresa’s parents are listed on all these documents, Giovanni’s parents are ignoto (“unknown”). His place of birth is listed as “the hospital of Pisa” which a little digging revealed to be the Spedali Riunti di Santa Chiara Trovatelli. In Italian, trovare means “to find”, and so a trovatello is a “little found thing/person”. Giovanni was a foundling, given up to the hospital by an anonymous mother the day after he was born.

Whilst this is was an exciting and touching little nugget of history, it did seem to rather spell doom for my hopes of ever working out the origin of my name. But then I remembered something I hadn’t really thought about since I was a Masters student first learning Latin. There is a Latin verb, omittere, which means “to leave behind”, “to let go”, “to give up”. Its past participle is omissus “left behind”. As a family name, that would be omissi. Back in 2009 this struck me as just an amusing coincidence. Now, however, I have cause to wonder. The Foundling Hospital of Pisa obviously had many clerics on its staff, all of whom would have been well versed in Latin. It was not uncommon for foundlings to be given names that indicated their dislocated origins: Esposito (“abandoned”), Innocenti (“innocent”), and Trovato (“found”) are examples of such. If, therefore, we translate my great great grandfather’s name into an English version, then Giovanni Omissi was little John Leftbehind.

This realisation then got me thinking further about my name in its entirety. Rather improbably, my name is Adrastos Omissi. But why Adrastos? Around the same time that I started learning Latin, I also started learning Greek (an enterprise that I think it’s fair to say I never really finished). I naturally therefore began to enquire about the meaning of my utterly absurd Classical Greek given name. Adrastos (Ἄδραστος), is a name composed of three parts. The initial α– (a–) is a negating prefix (think “asexual”, “asynchronous”, “anaerobic”), the central –δρασ– (–dras–) is a verbal stem derived from ἀποδιδράσκω (apodidraskō), to escape, and the –τος (–tos) is an ending that creates a verbal adjective. We can translate this name, therefore, as “the inescapable”. Adrasteia, remember, was the goddess off vengeance, Latin Nemesis, since vengeance is inescapable. The Homeric King Adrastos was said to have founded the first temple to Nemesis (Strabo, Geog. 13.1.13). Centuries later, Adrastos, son of the Phrygian king Gordias, was exiled by his father for accidentally killing his brother, and fled to the court of Croesus, king of Lydia. Croesus had dreamt a prophecy that his son Atys would be killed by an iron spear, and as a result had forbidden Atys ever to go to war. When a monstrous boar began to ravage Mysia, however, Atys convinced his father to send him out with the expedition to kill it, in the company of which was also Adrastos. The boar was cornered but Adrastos threw his spear wide of the mark and it struck Atys instead, killing him on the spot. An inescapable fate indeed (Hdt. 1.35-44).

But why, I hear you cry, would anyone who was not an ancient Greek, choose to name a child Adrastos in Jersey in the 1980s? Certainly it would be likely to bring upon the poor unfortunate creature (who also happened to be a skinny, bookish child with enormous glasses) a fairly “inescapable” amount of ridicule from other children (calling me “Asbestos”, I remember, was a favourite). I had never really understood, until I learned this etymology in my twenties. My name, I realised, was a rather off-colour joke on the part of a father who, at the time of my creation, was an unmarried second year undergraduate from an impoverished background, rather unexpectedly studying Greek as part of an English degree. Poor unplanned little accident that I was, he decided to leave a little message for me in the future, woven into my name. I was the inescapable fate, and armed now with what I believe is a highly plausible theory on the origins of my second name, the picture grows only more bleak, because it transpires that I am The-Inescapable Left-Behind.

We all have our crosses to bear…