One of the research projects currently underway in Classics at Glasgow is looking at the fragments of Roman oratory from the Republican period. This project (‘The Fragments of the Republican Roman Orators, www.frro.gla.ac.uk), funded by the European Research Council, aims to gather and make sense of all the evidence for public speech in the Republican period by orators other than Cicero.

Written oratory, like most other kinds of text from classical antiquity, depended for its survival on being included in a canon. Some authors, and some of their works, were read in schools and were considered ‘classics’; these were the texts that tended to be copied and still read after the end of antiquity and – with a few happy additions – they are the ones of which manuscripts survived down to the invention of printing. Cicero was the canonical author for oratory in Latin: so much so that no speeches by any other orator from the Roman Republic survived in an independent manuscript tradition. The fragments which we do possess are from quotations by later authors, who either had access to a copy of the speech in question or took the quotation from an earlier collection of excerpts.

This is a peculiarly frustrating state of affairs. Not just because we would like to have the speeches of Cicero’s predecessors and contemporaries, though we certainly would: what was it, for example, about Hortensius, who set the benchmark for oratory when Cicero began his career in the early 80s B.C.? Or about Licinius Calvus that made Catullus and an unknown bystander so excited when he spoke in the Forum (Cat. 53, di magni, salaputium disertum – loosely translated, OMG the runt can talk)? The gap also means we struggle to understand how politics worked in Republican Rome. We know that most political decisions were made after public debate followed by a vote. We also have a fair amount of evidence about occasions when what was said in the debate changed minds, and thus votes. But how did oratory have this effect? What was the balance between the character and the reputation of the speaker, and what he – and very occasionally she – actually said? What were the terms in which debate was framed: did speakers tend to appeal to the self-interest of their hearers or were ethical considerations prominent? Cicero was undoubtedly a very effective speaker, and so his speeches tell us a lot about what Roman audiences found persuasive; but we would like to know how representative he was.

So how is FRRO going to shed light on this problem? The fragments of Republican oratory – the words that seem to be quoted from texts of speeches – have been collected before, most recently in Malcovati’s great edition. What hasn’t been done systematically is to edit the testimonia for Republican oratory. Testimonia – information about public speech which does not include direct quotation – are important not simply because texts of speeches are lost, but also because many speeches never circulated in written form. (There was no automatic method of recording public speech verbatim in Rome, and many orators did not disseminate a written text of what they said after they had delivered their speech). If we look only at fragments, we get a skewed view of oratory, one directed towards orators who chose to record themselves – or we might even say, engage in self-promotion – by publishing their speeches and whose texts happened to appeal to later writers. (Gellius, for example, the antiquarian of the second century AD who is one of the most important sources of oratorical fragments, was particularly interested in earlier Roman orators – so we have big fragments of the elder Cato and Gaius Gracchus, but very little from Gellius about Cicero’s contemporaries). Once we put testimonia into the mix, we get a much bigger and broader picture.

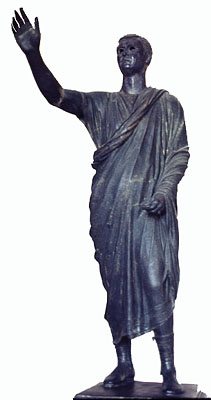

So what is emerging? One is a significant divide between being an orator in the law-courts – the equivalent of an advocate or barrister – and speaking as a necessary part of a public career as a magistrate and senator. The former was highly specialised and only some of those who were engaged in it were also pursuing a political career. But virtually any senior politician – broadly speaking, anyone who held the praetorship or consulship – might be required to speak to the people. In this respect (as in so many others) Cicero, who was a highly successful criminal advocate and a man who reached the top of the political ladder, was very unusual. Another conclusion we are reaching is that oratorical performance was absolutely key to decision-making, and that what was said is only part of the equation: how it was said and the actions that accompanied it are also vital. Orators needed to be able to weep, fall to the ground, invoke their dead parents and present their living children if what they said was to have its greatest effect. Even if most speeches, and most meetings, were very dull, the potential for wild excitement was always present.

As the project moves towards its conclusion, we are putting together an edition, with commentary and translation, of the Republican orators apart from Cicero and a database of speech in the Republic. As the diverse pieces of evidence fit together (or fail to) a much clearer and more detailed picture of how Roman public life worked is emerging, and we look forward to seeing what new questions and problems we can now address.